Effects of Trauma and Abuse on the Brain: Before and After Treatment

By Douglas Drossman, MD

Content Warning: physical and sexual abuse, trauma

Back in the 1980s, a patient came to me, a 12-year-old girl, who would inspire my research and ultimately change the way we understand the link between pain and trauma. Like many of my GI patients, she came to me with severe pain, constipation and multiple hospitalizations that affected her school life and social activities. I placed her on a bowel training treatment and saw her every 4 to 6 months in follow up visits. Over time, she responded positively to treatment. She had fewer absences, her grades improved, and she began to participate in normal activities.

Then, at age 16, she had a major life change. She started dating a 19-year-old and became sexually active. During one of her follow up visits, I noticed that she had changed. She was tearful, dropped out of cheerleading, and lost weight. She began to have horrible nightmares of being attacked. While we were talking during her exam, I uncovered that becoming sexually active had caused her to recall the sexual abuse she had suffered and repressed from age 3 to 7. The perpetrator was a family friend, and her family chose to handle the situation by pretending the abuse never happened. It was around this time that her abdominal pain and constipation began. I worked with her and her mother to get her the mental health support she needed, and with some medical interventions, her symptoms improved.

My training was in Gastroenterology and psychiatry, and after treating this patient, I began noticing a pattern: while taking histories of women coming to my practice, I discovered that a large number of them had suffered sexual or physical abuse in their past. To understand this better, we performed a survey in our gastroenterology clinic of over 200 women and found that 44% of women seeking treatment for severe GI disturbances reported a history of abuse. Only 11% of those women disclosed that treatment to their physicians. Doctors were treating patients without realizing the significance of how their past experiences affected their current health problems.

Next we studied severity of abuse history and its correlation to pain, and we began to understand that the more severe the abuse experience, the more severe the GI symptoms. In primary care, about 10 or 15 percent of patients report abusive experiences. However, for the women who sought referrals, nearly half had abuse experiences. I learned that those early traumatic experiences produced more severe symptoms and drove them to seek care.

This data led to an NIH grant producing research publications that spanned 25 years. For the first time in Western medicine, a team studied the link between trauma and symptom severity. We created a scale and assigned a number value based on abuse severity, ranging from an attempt at a sexual assault, to inappropriate touching, to the most severe, which was penetration. Our findings were dramatic. Those who reported the most severe forms of abuse also reported the highest pain scores. In addition to more pain, we found a direct correlation to higher rates of disability, more operations, more psychological problems, and more functional disorders.

We also created a set of survey questions relating to physical abuse as well, asking questions like “were you hit,” and “did you fear your life was in danger,” and we found the same results in physical abuse as we had in sexual abuse. The more severe the physical abuse, the worse the pain. Our study applied to specifically GI disorders, but today, we understand that our results are not specific to GI, but the pattern replicates across all kinds of conditions.

This brings us back to the 12-year-old patient I had seen years before. She had recovered but then in the mid 1990s, as an adult, she had begun to experience worsening symptoms after getting married, and being in an abusive marriage. She reported feeling out of control of both her symptoms and her life and began using increasingly higher doses of prescribed narcotics to treat her GI pain. I changed her over to neuromodulators, she began therapy, and with appropriate medical, therapeutic, and family support, she was ultimately able divorce her abusive spouse and again recover.

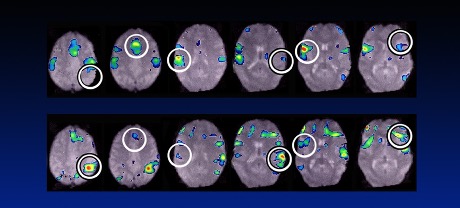

We had already discovered the connection between severe abuse and severe health problems, and we knew that patients weren’t doing this to themselves. I wanted to understand the mechanism in the brain to cause such severe pain in my patients, relative to patients who had not suffered past trauma. This led me to study brain images of the cingulate cortex and somatic sensory areas, or the pain centers of the brain. For the first time, we saw that something was happening in the brain of these patients experiencing pain.

In the slide below, the top image shows my patient’s brain during one of these painful episodes. The bottom row shows the same area of the brain after treatment. The pain she was experiencing after treatment was not as severe. In the brain image figure, the top row represents areas of the brain before treatment. The second and third brain images represent the very bright areas that are associated with pain. Note in the bottom row (after treatment) that the 2nd and 3rd images show much less brightness representing improvement and less pain. In a larger study, we confirmed that the brain scans of abused women show activation in the cingulate cortex that is greater than those without abuse history and this correlated with the degree of pain they experienced.

In other words, the pain is real. It is not all in the patient’s head and it’s not a psychiatric condition. My research shows that there is a physiological and structural change in the brain that causes more severe pain in victims of abuse and trauma. But my research also contains proof of a reason to be hopeful: brain scans of patients taken after treatment prove that these changes are reversible. If you or a loved one is suffering, I encourage you to seek treatment.

Resources and Further Reading

- To be speak with someone immediately and confidentially, call the National Sexual Assault Hotline at 1-866-656-HOPE

- To read and learn more about Dr. Drossman’s work and the Gut-Brain connection, visit

https://romedross.video/Q_ATrauma_Abuse

https://romedross.video/Q_ATrauma_Abuse2

https://romedross.video/Brain-GutAxis

- To find a Gastropsych professional near you, visit:

- Online resources for survivors of abuse: