Diet in Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

Magnus Simrén, Professor, University of Gothenburg, Sweden

Diet triggers symptoms in the vast majority of individuals with IBS. This has led to a growing interest in the role of diet in IBS and the use of dietary advice and specific diets to reduce patient symptoms. The most frequently used diets for IBS include traditional dietary advice, a lactose-free diet, a diet low in fermentable carbohydrates, i.e., the low fermentable oligo-, di-, monosaccharides and polyols (FODMAP), and a gluten-free diet (GFD). It is also quite common that patients use a “trial and error” approach to avoid food items that trigger symptoms.

Traditional IBS Dietary Advice

Traditional dietary advice is recommended as the first-line option. The evidence for this is weak, with recommendations based on clinical experience and knowledge about physiological effects of nutrients in the gastrointestinal tract. Recommendations include healthy eating and lifestyle management that involve regular meals, adjustment of fiber intake, adequate fluid intake, modest use of alcohol and caffeine, decreasing fat intake and assessing components of spicy meals, all of which may contribute to symptoms. Moreover, eating smaller and more frequent meals is also part of the traditional dietary advice.

Even though the scientific evidence base for this advice is weak, the clinical experience supports improved symptoms in a substantial proportion of individuals with IBS. In some recent trials, patients recommended to follow traditional dietary advice seem to do as well as patients who are advocated to follow a low FODMAP diet.

Low FODMAP Diet for IBS

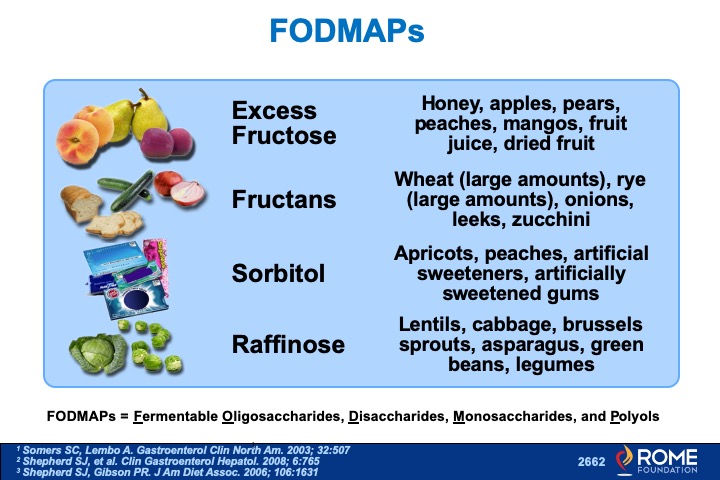

FODMAPs are carbohydrates that are not digested properly. They are poorly absorbed in the small intestine, and instead pass into the large intestine, where the carbohydrates interact with gut bacteria and gas is produced through fermentation. The carbohydrates also pull water into the intestine through osmosis. Taken together, these effects lead to distension of the bowel, and in a subject with a sensitive bowel, which is common among patients with IBS, lead to bowel symptoms. Therefore, avoiding or reducing intake of foods with high FODMAP content, i.e. following a low FODMAP diet, has been convincingly demonstrated to reduce symptom severity in a sizable proportion of the patients with IBS.

What are high-FODMAP foods?

High FODMAP-containing food includes grains, legumes, dairy products, certain fruits and vegetables, and foods and drinks sweetened with artificial sweeteners. This diet is not easy to follow and supervision from a properly trained dietician is recommended. The principle is to first restrict intake of foods high in FODMAPs for a period of at least four weeks. If a positive symptom response is noted during the restriction phase, the restricted food groups are gradually reintroduced in order to find a suitable long-term diet that is nutritionally adequate.

Following a strict low-FODMAP diet long-term, i.e. without reintroducing a proportion of the food items containing FODMAPs, is not recommended, as this seems to have non-beneficial effects on our gut bacteria composition. Concerns regarding negative health effects of long-term use of a low FODMAP diet have been raised.

Gluten-Free Diet (GFD) for IBS

The use of a GFD, outside of a known diagnosis of celiac disease, has been growing in popularity over the last decade. There is now evidence suggesting that a proportion of patients with IBS are sensitive to gluten or, in particular, to wheat-containing products. Therefore, more and more individuals with IBS use a diet low in or free of wheat and other grains, or even a totally GFD.

Although many of these patients report a good symptom reduction of these diets, the mechanism behind symptom improvement is less well established. The symptomatic benefit may be related to gluten and other constituents in grains that have effects on the immune system in the gut. However, the benefit might also be related to the carbohydrate content in grains, e.g. fructans with similar mechanism behind symptom generation as described above for FODMAPs.

The evidence base supporting the use of these diets in IBS is relatively weak, with mixed results in existing trials. More research is definitely needed before widespread recommendations of this diet can be advocated.

Conclusion

Food is central for patients with IBS, and giving patients advice on food and diet is an integral part of the management of these patients. Today, the evidence for current dietary recommendations is relatively weak, even though clinical experience and a small number of well-designed clinical trials support their use. However, more research on the effects of diet in IBS and the use of restrictive diets is needed to be able to give solid recommendations to patients. It is likely that the clinical response to diets differs among patients, so we hope that in the future, more personalized dietary advice will be possible.